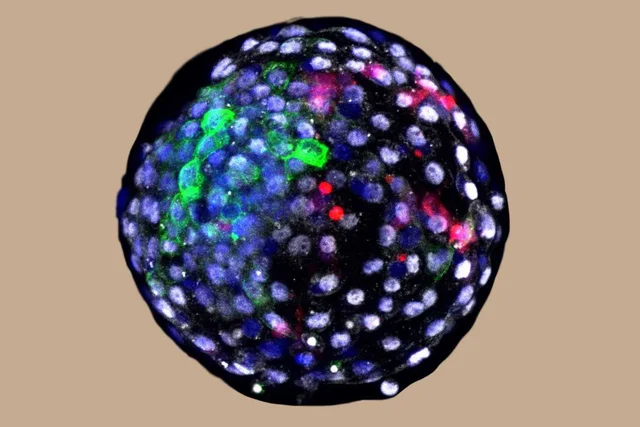

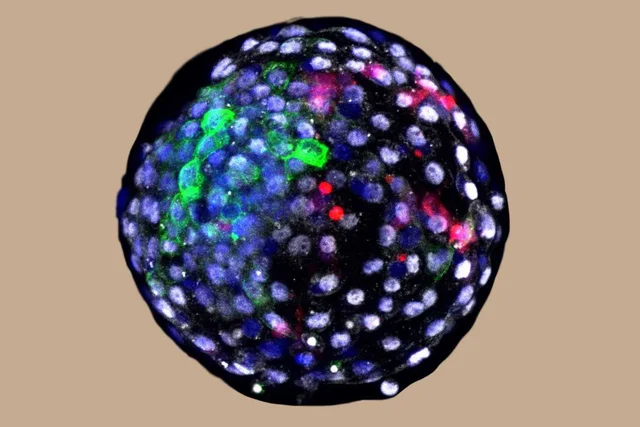

Esta imagen coloreada de una quimera blastoide muestra la bola hueca de células de dos especies que se parece mucho a un blastocisto, un embrión en la etapa de desarrollo cuando normalmente se implantaría en el útero. Weizhi Ji / Universidad de Ciencia y Tecnología de Kunming

Por primera vez, los científicos han creado embriones que son una mezcla de células humanas y de mono.

Los embriones, descritos el jueves en la revista Cell, fueron creados en parte para tratar de encontrar nuevas formas de producir órganos para personas que necesitan trasplantes, dice el equipo internacional de científicos que colaboró en el trabajo. Pero la investigación plantea una variedad de preocupaciones.

"Mi primera pregunta es: ¿Por qué?" dice Kirstin Matthews, miembro de ciencia y tecnología del Instituto Baker de la Universidad Rice. "Creo que el público estará preocupado, y yo también, de que estamos avanzando con la ciencia sin tener una conversación adecuada sobre lo que deberíamos o no deberíamos hacer".

Aún así, los científicos que llevaron a cabo la investigación y algunos otros bioeticistas defendieron el experimento.

"Este es uno de los principales problemas de la medicina: el trasplante de órganos", dice Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, profesor del Laboratorio de Expresión Genética del Instituto Salk de Ciencias Biológicas en La Jolla, California, y coautor de Cell estudio. "La demanda de eso es mucho mayor que la oferta".

"No veo que este tipo de investigación sea éticamente problemático", dice Insoo Hyun, bioético de la Universidad Case Western Reserve y la Universidad de Harvard. "Está dirigido a elevados objetivos humanitarios".

Miles de personas mueren cada año en los Estados Unidos esperando un trasplante de órgano, señala Hyun. Entonces, en los últimos años, algunos investigadores en los EE. UU. Y más allá han estado inyectando células madre humanas en embriones de ovejas y cerdos para ver si eventualmente podrían desarrollar órganos humanos en tales animales para trasplantes.

Pero hasta ahora, ese enfoque no ha funcionado. Así que Belmonte se asoció con científicos en China y en otros lugares para probar algo diferente. Los investigadores inyectaron 25 células conocidas como células madre pluripotentes inducidas de humanos, comúnmente llamadas células iPS, en embriones de monos macacos, que están mucho más relacionados genéticamente con los humanos que las ovejas y los cerdos.

Después de un día, informan los investigadores, pudieron detectar células humanas que crecían en 132 de los embriones y pudieron estudiar los embriones hasta por 19 días. Eso permitió a los científicos aprender más sobre cómo se comunican las células animales y las células humanas, un paso importante para eventualmente ayudar a los investigadores a encontrar nuevas formas de cultivar órganos para trasplantes en otros animales, dice Belmonte.

"Este conocimiento nos permitirá volver ahora y tratar de rediseñar estas vías que son exitosas para permitir el desarrollo apropiado de células humanas en estos otros animales", dice Belmonte a NPR. "Estamos muy, muy emocionados".

Estos embriones de especies mixtas se conocen como quimeras, nombradas así por la criatura que escupe fuego de la mitología griega que es en parte león, en parte cabra y en parte serpiente.

“Nuestro objetivo no es generar ningún organismo nuevo, ningún monstruo”, dice Belmonte. "Y no estamos haciendo nada de eso. Estamos tratando de entender cómo las células de diferentes organismos se comunican entre sí".

Además, Belmonte espera que este tipo de trabajo pueda conducir a nuevos conocimientos sobre el desarrollo humano temprano, el envejecimiento y las causas subyacentes del cáncer y otras enfermedades.

Algunos otros científicos de NPR con los que hablaron están de acuerdo en que la investigación podría ser muy útil.

"Este trabajo es un paso importante que proporciona evidencia muy convincente de que algún día, cuando comprendamos completamente cuál es el proceso, podríamos hacer que se desarrollen en un corazón, un riñón o pulmones", dice el Dr. Jeffrey Platt, profesor de microbiología e inmunología en la Universidad de Michigan, que está realizando experimentos relacionados pero no participó en la nueva investigación.

Pero este tipo de trabajo científico y las posibilidades que abre plantea serias dudas para algunos especialistas en ética. La mayor preocupación, dicen, es que alguien pueda intentar llevar este trabajo más allá e intentar hacer un bebé a partir de un embrión creado de esta manera. Específicamente, a los críticos les preocupa que las células humanas puedan convertirse en parte del cerebro en desarrollo de un embrión así y del cerebro del animal resultante.

"¿Debería regularse como humano porque tiene una proporción significativa de células humanas en él? ¿O debería regularse solo como un animal? ¿O algo más?" dice Matthews. "¿En qué momento estás tomando algo y usándolo para órganos cuando en realidad está comenzando a pensar y tener lógica?"

Otra preocupación es que el uso de células humanas de esta manera podría producir animales que tengan espermatozoides u óvulos humanos.

"Nadie realmente quiere que los monos anden con óvulos humanos y esperma humano dentro", dice Hank Greely, un bioético de la Universidad de Stanford, quien coescribió un artículo en el mismo número de la revista que critica la línea de investigación, al tiempo que señala que esto un estudio particular se hizo éticamente. "Porque si un mono con esperma humano se encuentra con un mono con óvulos humanos, nadie quiere un embrión humano dentro del útero de un mono".

Belmonte reconoce las preocupaciones éticas. Pero enfatiza que su equipo no tiene la intención de intentar crear animales con embriones en parte humanos y en parte de mono, o incluso tratar de hacer crecer órganos humanos en una especie tan estrechamente relacionada. Dice que su equipo consultó de cerca con bioeticistas, incluida Greely.

Greely dice que espera que el trabajo estimule un debate más general sobre hasta dónde se les debería permitir llegar a los científicos con este tipo de investigación.

"No creo que estemos en el límite más allá del Planeta de los Simios. Creo que los científicos rebeldes son pocos y distantes entre sí. Pero no son cero", dice Greely. "Así que creo que es un momento apropiado para que comencemos a pensar, '¿Deberíamos dejar que esto vaya más allá de una placa de Petri?' "

Durante varios años, los Institutos Nacionales de Salud han estado sopesando la idea de levantar la prohibición de financiar este tipo de investigación, pero han estado esperando nuevas pautas, que se espera que salgan el próximo mes, de la Sociedad Internacional de Investigación con células madre.

La noción de utilizar órganos de animales para trasplantes también ha suscitado durante mucho tiempo preocupaciones sobre la propagación de virus de animales a humanos. Por lo tanto, si la investigación actual da frutos, se deberían tomar medidas para reducir ese riesgo de infección, dicen los científicos, como secuestrar cuidadosamente los animales utilizados para ese propósito y examinar cualquier órgano utilizado para el trasplante.

Copyright 2021 NPR. Para ver más, visite NPR.

https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(21)00305-6

Scientists Create Early Embryos That Are Part Human, Part Monkey

For the first time, scientists have created embryos that are a mix of human and monkey cells.

The embryos, described Thursday in the journal Cell, were created in part to try to find new ways to produce organs for people who need transplants, says the international team of scientists who collaborated in the work. But the research raises a variety of concerns.

"My first question is: Why?" says Kirstin Matthews, a fellow for science and technology at Rice University's Baker Institute. "I think the public is going to be concerned, and I am as well, that we're just kind of pushing forward with science without having a proper conversation about what we should or should not do."

Still, the scientists who conducted the research, and some other bioethicists defended the experiment.

"This is one of the major problems in medicine - organ transplantation," says Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a professor in the Gene Expression Laboratory of the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences in La Jolla, Calif., and a co-author of the Cell study. "The demand for that is much higher than the supply."

"I don't see this type of research being ethically problematic," says Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University and Harvard University. "It's aimed at lofty humanitarian goals."

Thousands of people die every year in the United States waiting for an organ transplant, Hyun notes. So, in recent years, some researchers in the U.S. and beyond have been injecting human stem cells into sheep and pig embryos to see if they might eventually grow human organs in such animals for transplantation.

But so far, that approach hasn't worked. So Belmonte teamed up with scientists in China and elsewhere to try something different. The researchers injected 25 cells known as induced pluripotent stem cells from humans - commonly called iPS cells - into embryos from macaque monkeys, which are much more closely genetically related to humans than are sheep and pigs.

After one day, the researchers report, they were able to detect human cells growing in 132 of the embryos, and were able study the embryos for up to 19 days. That enabled the scientists to learn more about how animal cells and human cells communicate, an important step toward eventually helping researchers find new ways to grow organs for transplantation in other animals, Belmonte says.

"This knowledge will allow us to go back now and try to re-engineer these pathways that are successful for allowing appropriate development of human cells in these other animals," Belmonte tells NPR. "We are very, very excited."

Such mixed-species embryos are known as chimeras, named for the fire-breathing creature from Greek mythology that is part-lion, part-goat, part-snake.

"Our goal is not to generate any new organism, any monster," Belmonte says. "And we are not doing anything like that. We are trying to understand how cells from different organisms communicate with one another."

In addition, Belmonte hopes this kind of work could lead to new insights into early human development, aging and the underlying causes of cancer and other disease.

Some other scientists NPR spoke with agree the research could be very useful.

"This work is an important step that provides very compelling evidence that someday when we understand fully what the process is we could make them develop into a heart or a kidney or lungs," says Dr. Jeffrey Platt, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan, who is doing related experiments but was not involved in the new research.

But this type of scientific work and the possibilities it opens up raises serious questions for some ethicists. The biggest concern, they say, is that someone could try to take this work further and attempt to make a baby out of an embryo made this way. Specifically, the critics worry that human cells could become part of the developing brain of such an embryo - and of the brain of the resulting animal.

"Should it be regulated as human because it has a significant proportion of human cells in it? Or should it be regulated just as an animal? Or something else?" says Matthews. "At what point are you taking something and using it for organs when it actually is starting to think, and have logic?"

Another concern is that using human cells in this way could produce animals that have human sperm or eggs.

"Nobody really wants monkeys walking around with human eggs and human sperm inside them," says Hank Greely, a Stanford University bioethicist, who co-wrote an article in the same issue of the journal that critiques the line of research, while noting that this particular study was ethically done. "Because if a monkey with human sperm meets a monkey with human eggs, nobody wants a human embryo inside a monkey's uterus."

Belmonte acknowledges the ethical concerns. But he stresses that his team has no intention of trying to create animals with the part-human, part-monkey embryos, or to even try to grow human organs in such a closely related species. He says his team consulted closely with bioethicists, including Greely.

Greely says he hopes the work will spur a more general debate about how far scientists should be allowed to go with this kind of research.

"I don't think we're on the edge of beyond the Planet of the Apes. I think rogue scientists are few and far between. But they're not zero," Greely says. "So I do think it's an appropriate time for us to start thinking about, 'Should we ever let these go beyond a petri dish?' "

For several years, the National Institutes of Health has been weighing the idea of lifting a ban on funding for this kind of research, but has been waiting for new guidelines, which are expected to come out next month, from the International Society for Stem Cell Research.

The notion of using organs from animals for transplants has also long raised concerns about spreading viruses from animals to humans. So, if the current research comes to fruition, steps would have to be taken to reduce that infection risk, scientists say, such as carefully sequestering animals used for that purpose and screening any organs used for transplantation.

Los científicos crean embriones tempranos que son en parte humanos y en parte mono

Rob Stein...

"Title of this article :" Chimeric contribution of human extended pluripotent stem cells to monkey embryos ex vivo: Cell... "

Imagen

Scientists Create Early Embryos That Are Part Human, Part Monkey

For the first time, scientists have created embryos that are a mix of human and monkey cells.

The embryos, described Thursday in the journal Cell, were created in part to try to find new ways to produce organs for people who need transplants, says the international team of scientists who collaborated in the work. But the research raises a variety of concerns.

"My first question is: Why?" says Kirstin Matthews, a fellow for science and technology at Rice University's Baker Institute. "I think the public is going to be concerned, and I am as well, that we're just kind of pushing forward with science without having a proper conversation about what we should or should not do."

Still, the scientists who conducted the research, and some other bioethicists defended the experiment.

"This is one of the major problems in medicine - organ transplantation," says Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a professor in the Gene Expression Laboratory of the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences in La Jolla, Calif., and a co-author of the Cell study. "The demand for that is much higher than the supply."

"I don't see this type of research being ethically problematic," says Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University and Harvard University. "It's aimed at lofty humanitarian goals."

Thousands of people die every year in the United States waiting for an organ transplant, Hyun notes. So, in recent years, some researchers in the U.S. and beyond have been injecting human stem cells into sheep and pig embryos to see if they might eventually grow human organs in such animals for transplantation.

But so far, that approach hasn't worked. So Belmonte teamed up with scientists in China and elsewhere to try something different. The researchers injected 25 cells known as induced pluripotent stem cells from humans - commonly called iPS cells - into embryos from macaque monkeys, which are much more closely genetically related to humans than are sheep and pigs.

After one day, the researchers report, they were able to detect human cells growing in 132 of the embryos, and were able study the embryos for up to 19 days. That enabled the scientists to learn more about how animal cells and human cells communicate, an important step toward eventually helping researchers find new ways to grow organs for transplantation in other animals, Belmonte says.

"This knowledge will allow us to go back now and try to re-engineer these pathways that are successful for allowing appropriate development of human cells in these other animals," Belmonte tells NPR. "We are very, very excited."

Such mixed-species embryos are known as chimeras, named for the fire-breathing creature from Greek mythology that is part-lion, part-goat, part-snake.

"Our goal is not to generate any new organism, any monster," Belmonte says. "And we are not doing anything like that. We are trying to understand how cells from different organisms communicate with one another."

In addition, Belmonte hopes this kind of work could lead to new insights into early human development, aging and the underlying causes of cancer and other disease.

Some other scientists NPR spoke with agree the research could be very useful.

"This work is an important step that provides very compelling evidence that someday when we understand fully what the process is we could make them develop into a heart or a kidney or lungs," says Dr. Jeffrey Platt, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan, who is doing related experiments but was not involved in the new research.

But this type of scientific work and the possibilities it opens up raises serious questions for some ethicists. The biggest concern, they say, is that someone could try to take this work further and attempt to make a baby out of an embryo made this way. Specifically, the critics worry that human cells could become part of the developing brain of such an embryo - and of the brain of the resulting animal.

"Should it be regulated as human because it has a significant proportion of human cells in it? Or should it be regulated just as an animal? Or something else?" says Matthews. "At what point are you taking something and using it for organs when it actually is starting to think, and have logic?"

Another concern is that using human cells in this way could produce animals that have human sperm or eggs.

"Nobody really wants monkeys walking around with human eggs and human sperm inside them," says Hank Greely, a Stanford University bioethicist, who co-wrote an article in the same issue of the journal that critiques the line of research, while noting that this particular study was ethically done. "Because if a monkey with human sperm meets a monkey with human eggs, nobody wants a human embryo inside a monkey's uterus."

Belmonte acknowledges the ethical concerns. But he stresses that his team has no intention of trying to create animals with the part-human, part-monkey embryos, or to even try to grow human organs in such a closely related species. He says his team consulted closely with bioethicists, including Greely.

Greely says he hopes the work will spur a more general debate about how far scientists should be allowed to go with this kind of research.

"I don't think we're on the edge of beyond the Planet of the Apes. I think rogue scientists are few and far between. But they're not zero," Greely says. "So I do think it's an appropriate time for us to start thinking about, 'Should we ever let these go beyond a petri dish?' "

For several years, the National Institutes of Health has been weighing the idea of lifting a ban on funding for this kind of research, but has been waiting for new guidelines, which are expected to come out next month, from the International Society for Stem Cell Research.

The notion of using organs from animals for transplants has also long raised concerns about spreading viruses from animals to humans. So, if the current research comes to fruition, steps would have to be taken to reduce that infection risk, scientists say, such as carefully sequestering animals used for that purpose and screening any organs used for transplantation.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)